Attitudes to risk – we find differences but also consistency over time in a volatile world

Do differences in income, age and sex lead to differences in risk appetite? And do turbulent world events shape our attitudes to financial risk? The A2Risk/YouGov survey investigates.

Income, age and sex – spotting the real differences

The survey carried out earlier this year, using A2Risk’s Attitude to Risk Questionnaire (ATRQ), scored 2,400 individuals for their risk attitude with scores ranging from 0 (extremely low risk appetite) to 40 (extremely high). The average score was 19.2.

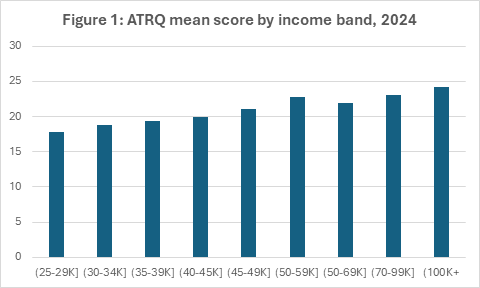

The survey revealed differing risk appetites across income, age and sex. As income rises, people’s appetite for risk also generally increases – see Figure 1. Those with incomes below £35,0001 had below-average risk attitude scores, while those with incomes above £35,000 had above-average risk attitude scores.

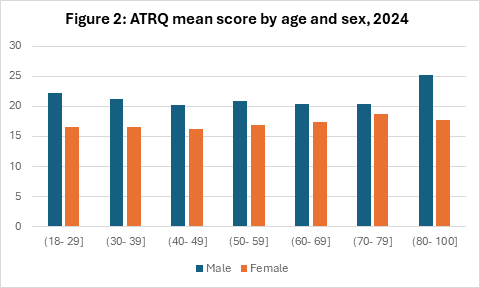

Figure 2 shows that, for men between 30 and 79, risk appetite is fairly constant, averaging 20.6. It appears to be higher for those below 30 and above 80, but the sample size for these age ranges is quite small, so the estimates are not reliable. So we can conclude that at the age ranges relevant for financial advisers, the typical risk appetite score for men is not age-sensitive.

The survey indicates that women are less risk tolerant than men in all age ranges, although risk tolerance does increase with age for women in the 50-79 age range. The same caveats apply to women below 30 and above 80 as for men.

While the average score for men between 30 and 79 was 20.6, it was 17.1 for women. This would appear to confirm the long-standing belief that women are financially more risk averse than men. However, when we control for income differences, the differences in risk attitudes between the sexes shrinks significantly. In other words, a typical man and woman with the same salary will have broadly similar financial risk appetites.

Interestingly this finding chimes with the results of an academic study into loss aversion carried out in 2021. Attitude to risk and loss aversion are not the same but are closely related. Raw data from that study (Quantifying loss aversion: evidence from a UK population study) showed a similar marked difference between men and women’s aversion to loss as the current survey does to aversion to risk. But when all factors were taken into account (for example, income or parental status), the difference between men and women ceased to be statistically significant.2

Remarkable stability over time

The last 14 years have been some of the most turbulent in living memory. The UK has been buffeted by the Global Financial Crisis, recessions, division and uncertainty over Brexit, the outbreak of war in Ukraine and a sharp spike in inflation and interest rates. But despite this, people’s attitude to risk has remained remarkably stable and consistent.

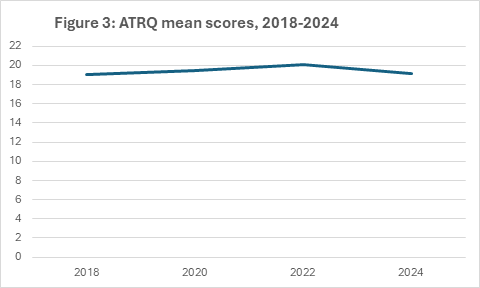

The 2024 survey average risk attitude score of 19.2 is very close to the average of 19.5 for all surveys since 2018 – see Figure 3. The survey is run every two years.

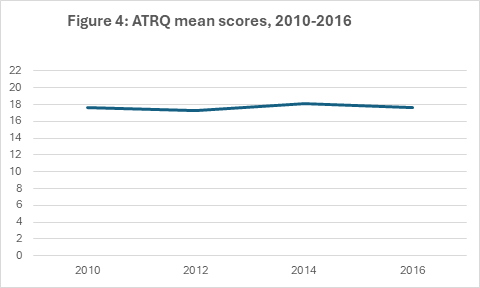

Between 2010 and 2016, a different research sample was used that included lower income individuals. This led to lower overall risk attitude scores for that period. Nevertheless, the figures across that period were also very stable, averaging 17.7 – see Figure 4.

The only significant blip across the entire 14-year period occurred in 2022 as the world emerged from the global Covid-19 pandemic, when the average rose to 20.1. The relief and optimism following a once-in-a-generation crisis seems natural, but it is equally telling that it left no lasting effect as risk appetites quickly returned to their long-term average.

The overall stability in the attitude to risk scores over such a long period (controlling for the structural break in the data from 2018) is really quite remarkable.

In the big picture, it’s still the individual that matters

Despite the questionnaire asking respondents about their current attitude to risk, the long-term stability in the responses suggests that a respondent’s risk score can also be used to guide long-term investment choices, such as those in a pension fund. Average figures can also inform the debate about how the financial sector should think about its customers.

However, it is important to remember that averages can conceal a wide range of differences in the individual scores across incomes, ages and sexes. Further the average respondent in one survey may not be the same person as the average respondent in another survey.

The findings therefore show the importance of considering an array of factors in assessing attitude to risk for any one individual – as well as comparing the results for that individual against the average.

Knowledge of both the individual and the average score can be used by the adviser to encourage an individual who is extremely risk averse to take on more financial risk in their pension fund than they would initially be comfortable with. This would enable those with a ‘recklessly conservative’ risk attitude to achieve a higher long-run average return on their pension savings.

That individual assessment is, of course, the real value of the ATRQ.